There are many misconceptions about in season hockey training for athletes ages 14 to 18. Note: we’re not talking about an NHL player. Programming is completely different for professional players (full grown adults), compared to programming for a developing teenage athlete. This population should constantly be focused on putting on lean mass and getting stronger. If they’re not, then they are missing out on a crucial period of development.

Common Misconceptions:

· In season is time to maintain strength (14-21 y/o)

· Train for speed in the gym (plyometrics and/or sprinting)

· Train “sport specific” work

· Don’t squat or deadlift in season

· Use light weights in season

MISCONCEPTION: In season is the time to maintain strength (14-21).

OUR APPROACH: Developing strength and continuing to put on muscle mass (hypertrophy) are the two most important things for in season hockey players between the ages of 14 and 21.

MISCONCEPTION: Train for speed in the gym (plyometrics and/or sprinting).

OUR APPROACH: Speed qualities are already being addressed. Every shift, every practice, and skill session has a speed component attached to it. It is important to know that although speed is being trained, strength and hypertrophy are not being addressed.

MISCONCEPTION: Train “sport specific” exercises in season.

OUR APPROACH: There is no need for sport specific work in season. There is nothing more sport specific than being in season.

MISCONCEPTION: Don’t squat or deadlift in season.

OUR APPROACH: Use complex movements. We understand that time is limited. For this reason, our in-season workouts are programmed with exercises that give you the biggest bang for your buck. Exercises such as squats, deadlifts, presses, chin up variations and Olympic lifting variations will do just that. The reason being is that when athletes train these movements, they also work secondary muscles as well.

MISCONCEPTION: Use lighter weights and take off from lifting while feeling rundown during the season.

OUR APPROACH: Frequency (days per week) and intensity should remain constant. The one variable that can be manipulated is volume. Volume (sets) can be decreased based on how the athlete feels.Simply decreasing the weight will compromise the intended result. That being said, it is important to know that every exercise has an effect. Athletes who are feeling rundown should decrease the total number of sets (volume) while maintaining the weight (intensity). This will ensure that you will get the results you’re looking for.

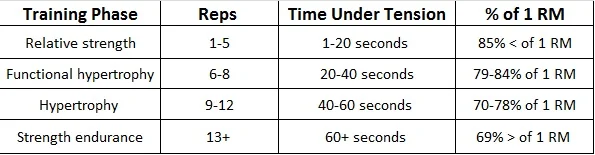

The number one cause of injury is fatigue. The goal is to keep our athletes fresh, healthy, and energized throughout the season. We take our workouts day by day, week by week. We do so by communicating with our athletes prior to every workout. It is important for each athlete to be honest with themselves and for coaches to be flexible with their individual assessment. We use the table presented below to manipulate the workload for the day.

When our athletes express that they have low energy, aren’t recovering well, and/or are rundown, we reduce the number of sets (volume) – NOT THE WEIGHT (intensity). All other variables remain constant: reps, rest, weight. Below are two sample exercises, one for strength and one for hypertrophy. Athletes are required to complete 3, 4, or 5 sets of snatch grip deadlift or 2, 3, or 4 sets of back squats. Both programs hold all other variables constant regardless of the number of sets.